Water

last authored:

last reviewed:

Introduction

Water is an extremely important molecule that contributes to most body functions.

Water Content in the Body

Water constitutes 50-60% of total body weight, but varies with amount of body fat, linked to age, gender, and nutritional status.

Total Body Water (TBW) = 0.6 x wt(kg) for men and 0.5 x wt(kg) for women

Approximately 2/3 of water is intracellular, while of the remainder, 3/4 is in the interstitial space and 1/4 is in the plasma.

The solute content of body water is tightly controlled between 285-295 mOsm/kg of water. Cell membranes provide a barrier between the compartments. Because membranes are relatively permeable to water, osmotic gradient determines fluid shift.

Water Intake and Output

Water intake occurs throughout the gastrointestinal system, and is lost in the stool, through respiration, persiration, and especially in the urine.

- ins and outs

- water and the GI system

- water and the kidneys

Ins and Outs

Important physiologic measure.

Water Flow through the GI System

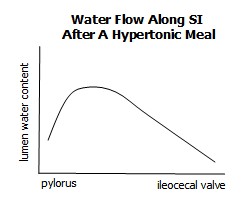

The SI encounters 9L of water daily, comprised of dietary intake, secretion of gastric and pancreatic juice, bile, and through osmotic movement. Osmotic flow is the largest contributor and is prominent immediately after a hypertonic meal.

Inflow |

Outflow |

|---|---|

Food: 2.0 L |

|

Saliva: 1.5 L |

|

Gastric Secretion: 2.0 L |

|

Pancreatic Secretion: 1.5 L |

|

Bile Secretion: 0.5 L |

|

SI Secretion: 1 L |

SI Absorption: 6.5 L |

LI Absorption: 2.0 L |

|

total input: 8-10 L |

stool excretion: 100-150 ml |

Small Intestine Water Secretion and Absorption

Water is secreted from the Crypts of Lieberkuhn by passive diffusion, drawn out by osmotic pressure following a hypertonic meal. It is can travel either paracellularly or transcellularly. As always, water travels to areas of highest soulte concentration.

Water is secreted from the Crypts of Lieberkuhn by passive diffusion, drawn out by osmotic pressure following a hypertonic meal. It is can travel either paracellularly or transcellularly. As always, water travels to areas of highest soulte concentration.

Water absorption follows sodium absorption, which is coupled with the intake of digested nutrients. As Na (and the Cl that follows) is drawn into cells and pumped, via the Na/K pump, into the interstitium, water follows. A buildup of hyrdostatic pressuremoves water into the capillaries.

Paracellular water absorption is most effective in the duodenum due to its less rigorous tight junctions.

Normally the SI absorbs 6.5 L of water daily, but if needed, it can absorb up to 20 L/day. The large intestine normally absorbs 2 L daily, if needed, the LI can absorb up to 3-4 L/day.

Lactose Intolerance

In people who are lactose intolerant, lactose is not digested and remains trapped in the lumen. This pulls water along the GI tract with it, and when lactose is digested by bacteria in the colon, this increase in solute concentration pulls even more water out, leading to explosive diarrhea.

Water and the Kidneys

The kidneys play a crucial role in regulating extracellular fluid volume. Blood pressure is maintained along with the hemodynamic responses cardiac output and total peripheral resistance.

After 25% of blood flow is filtered through the glomerulus, most water is reabsorbed by the nephron. At least 60% occurs in the proximal tubule.

The primary renal response is to adjust external sodium and water balance. It invloves various hormones and can take 12-24 hours. Extrarenal baroreceptors results in release of ADH, promoting water retention.

Vasodilatory prostaglandins such as PGE2 enhance renal blood flow and GFR.

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) is a major factor promoting natriuresis in volume-expanded states.

As only 15% of blood volume is in the arteries,

The Biochemistry of Water

Water is a V-shaped molecule with a bond angle of 104.5o between its O-H bonds. An oxygen atom has six electrons in its outer shell, facilitating formation of two covalent bonds. As oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, oxygen bears a partial negative charge and hydrogen a partial positive charge, making water a polar molecule even though it is electrically neutral. The physical properties of water allow it to form weak hydrogen bonds with itself and other molecules.

Water as a Solvent

The polarity of water allows it to interact with, and dissolve, other polar compunds. Electrolytes, such as sodium or chloride, dissociate from one another in the presence of multiple hydrogen bonds, leading them to become solvated.

Any polar molecules has a tendency to dissolve in water, with the number of polar groups determining solubility.

Osmosis is the movement of solvent across a membrane from areas of higher solvent concentration to areas of lower concentration. Pure water has a concentration of 55.5M. Osmotic pressure is the pressure required to prevent solvent flow, and depends on molar solute concentration, not chemical properties.

Nonpolar substances such as hydrocarbons are poorly soluble in water, leading them to associate with each other. Chaotropes enhance the solubility of nonpolar molecules in water by disordering water molecules.

Amphipathic molecules, such as detergents (surfactants), are both hydrophobic and hydrophilic, form monolayers or micelles in the presence of polar solvents such as water.

Water and Bond Formation/Degradation

Water is nucleophilic, meaning it is electron-rich and attrachted to positively charged electrophilic molecules. Hydrolysis occurs following nucleophilic attack of water molecules.

In many molecules, such as proteins, hydrolysis is more energetically favorable than bond formation, requiring ATP, and often many steps, for molecule synthesis.

Ionization of Water

Water has a slight tendency to ionize: 2 H20 -> H30+ + OH- Hydronium ions have the ability to donate protons to other molecules, making them acids. The equilbrium constant is defined as

Keq = [H+][OH-] / [H2O]

As in pure water [H+] = [OH-], its pH = 7.