Escherichia coli

last authored: July 2011, Erica Rubin

last reviewed: July 2011, Eugenie Waters

Introduction

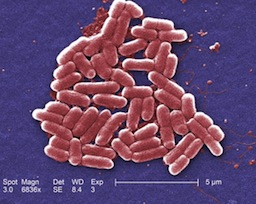

E coli, courtesy of CDC PHIL # 10068

Escherichia coli is a gram negative bacillus from the Enterobacteriaceae family. It is one of the enteric bacteria, meaning it colonizes the intestines. In fact, it is not normally found outside of the GI tract. All humans are colonized with E. Coli, and generally it is not pathogenic. However, through swapping DNA with other bacteria, it can acquire virulence factors and cause disease.

The Case of Samantha R.

Samantha is an 18 year old girl presents to your office with a 3 day history of watery diarrhea, malaise, nausea, vomiting, and cramps. She has just returned from a one week school trip to Mexico, where she was volunteering at an orphanage. The vomiting started on the last day of her trip, and was quickly followed by several episodes of non-bloody, watery diarrhea per day. She has had very little appetite, but is managing to drink plenty of fluids.

On questioning, she says that she and several of her classmates stayed at the orphanage and ate the same foods that the children ate. A few of her classmates were also ill.

On exam, vital signs are normal and temperature is 37 degrees Celsius. Mucous membranes are somewhat dry. The abdomen is soft and non-tender.

- What pathogens are you concerned about?

- How would you approach her diagnosis?

- What treatments would you offer?

Epidemiology

E coli is ubiquitous, being the most aerobic, gram-negative bacillus in the gastrointestinal tract. Most infections are caused by endogenous bacteria. Pathogenic strains occur in outbreaks around the world, with reservoirs in animals such as cattle. Recent outbreaks include:

- Germany, 2011 - contaminated vegetables

- United States, 2006-2011 - contaminated foods

- Walkerton, Canada, 2000 - contaminated town water

Classification and Characteristics

E. Coli is a gram negative bacillus, and is part of the Enterobacteriaceae family. It is normally non-pathogenic, but can acquire virulence factors from other bacteria, which allow it to cause disease. E. coli can be classified according to which virulence factors it acquires.

The following classes of E. coli all cause diarrhea, along with their virulence factors:

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

|

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC):

|

Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC):

|

There are a few other classes which affect primarily developing countries.

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) is particularly pathogenic in regards to urinary tract infections. It has acquired a pili virulence factor, which allows it to adhere to uroepithelial cells.

Transmission and Infection

E. coli is normally found only in the intestine, so it is transmitted through contact with feces. Vectors commonly include contaminated food and water in the case of gastroenteritis.

Clinical Manifesations

Diseases caused by E. coli include:

- Diarrhea

- Urinary tract infection

- Neonatal meningitis

- Gram-negative sepsis in hospitalized patients

Diarrhea

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

ETEC is the most common cause of traveler's diarrhea. Diarrhea is common in travel to developing countries due to poor water sanitation. Water becomes contaminated with E. coli when it has come into contact with human or animal feces. Therefore, travelers are cautioned to drink only bottled water, and avoid fresh fruits and vegetables which may have been washed with the water. High risk areas include parts of Asia, Africa, South and Central America, and Mexico.

As mentioned above, ETEC has acquired the pili virulence factor, so it is able to attach to intestinal epithelial cells. Its LT and ST virulence factors allow it to secrete toxins which alter the electrolyte secretion of intestinal cells. They inhibit the reabsorption of Na+ and Cl-, and stimulate the secretion of Cl- and HCO3-. Water follows and produces watery diarrhea, which looks like rice water.

This disease is benign and usually self-limited, however complications, including death, can occur from dehydration. Symptoms include malaise, anorexia, abdominal cramps, and watery diarrhea. These can be accompanied by nausea and vomiting, as well as a low grade fever. Symptoms usually last for 1 to 5 days.

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)

E coli 0157 with flagella (motility virulence factor)

courtesy of CDC PHIL, #9995

EHEC contains the pili virulence factor, as well as the Shiga-like toxin virulence factor. This toxin inhibits protein synthesis of the intestinal epithelial cells, thereby causing cell death. The diarrhea caused by EHEC is, therefore, bloody. It is usually accompanied by severe abdominal cramps.

An example of EHEC is E. coli 0157:H7 - the strain which is known for causing food poisoning from undercooked hamburger, as well as the Walkerton tragedy. This strain is associated with the development of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). The 2011 E. coli outbreak in Germany was caused by EHEC 0104:H4.

Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC)

EIEC contains the Shiga-like toxin, so the diarrhea is also bloody. It also contains a virulence factor which allows it to invade the intestinal epithelial cells. As a result, there is a systemic inflammatory response, causing fevers, as well as white cells in the stool.

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

The pili of UPEC allow E. coli from the stool to adhere to uroepithelial cells in the urethra and bladder. Bladder infection is called 'cystitis'. Clinical manifestations include urinary frequency, dysuria, suprapubic tenderness, and foul-smelling or cloudy urine. Symptoms suggesting the infection may have ascended to the kidneys (pyelonephritis) include fever, nausea and vomiting, and costovertebral angle tenderness.

Neonatal Meningitis

Meningitis in the neonatal period (usually the first month of life) is often caused by infection acquired through the birth canal. Fecal contamination is common, therefore E. coli is the second most common bacterial cause of neonatal meningitis (after Group B Streptococcus). Clinical manifestations include fever (or hypothermia), poor feeding, irritability or lethargy, hepatic dysfunction, and hypotension. Later on, seizures, nuchal rigidity, bulging fontanelle, increased/decreased tone, gaze deviations, and other neurologic abnormalities may occur. Respiratory symptoms may also be present. However, fever is often the only sign.

Gram Negative Sepsis

E. coli must also be considered when bacteremia or pneumonia occurs in debilitated hospitalized patients. Septic shock is thought to occur due to the lipid A component of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or endotoxin of gram negative organisms.

Diagnosis

Diarrhea

Pathogenic E. coli cannot be distinguished from non-pathogenic E. coli on stool culture, therefore diarrhea is often treated empirically based on the most likely organisms. Stool can be sent for culture, as well as for ova and parasites, to rule out other pathogens.

UTI

UTI is diagnosed by urine culture. Presence of a UTI can be suggested by urine dipstick, which will usually show positive leukocyte esterase, positive nitrites, with or without positive red blood cells. Often a culture is unnecessary, unless the UTI is recurrent, the symptoms are uncharacteristic or suggest complicated infection, or the symptoms occur within a month of antibiotic treatment. Cultures are useful to determine susceptibilities in the case of resistant strains of E. coli.

Neonatal Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis is confirmed by isolation of a pathogen on CSF culture. CSF culture may be negative if antibiotics were administered before the lumbar puncture was done. In this case, certain features of the CSF are sufficient to diagnose bacterial infection. These include:

- WBC count >20-30 cells/microlitre

- protein >100mg/dL

- glucose <30mg/dL (1.7mmol/L)

- positive gram stain

Infants with suspected meningitis should also undergo a full septic work-up, including urine and blood cultures. Given the seriousness of the consequences of sepsis and/or meningitis, they should be treated empirically.

Treatments

Antibiotics used to treat E. coli include: third generation cephalosporins (for pneumonia, meningitis, pyelonephritis), aminoglycosides (cover pseudomonas), fluoroquinolones (complicated UTIs, diarrhea), and TMP/SMX (UTIs).

Diarrhea:

Given that ETEC is the most common cause of traveler's diarrhea, and cannot be differentiated from non-pathogenic E. coli on stool culture, it is typically treated empirically with a quinolone, such as ciprofloxacin, for 1-2 days. This has been shown to reduce symptom duration to about one day. Dehydration is the most worrisome complication, so fluid replacement is of utmost importance. Anti-motility drugs, such as loperamide, can be used to decrease the severity of diarrhea. Traveler's diarrhea which presents with severe upper GI symptoms is less likely to be caused by ETEC, and warrants sending stool for culture, ova, and parasites.

Diarrhea which is unrelated to travel may be caused by a wide variety of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and parasites. Treatment will differ depending on the most likely organism. Diarrhea due to E. coli can be treated with a quinolone (such as ciprofloxacin), or azithromycin. It is important to note that using antimotility agents to treat the diarrhea associated with EHEC may increase the length of the illness. Therefore, typically antimotility agents should not be used for bloody diarrhea.

UTI:

UTIs may be treated empirically, especially if urine dip is suggestive of infection. Uncomplicated urinary tract infections can be treated with TMP/SMX (Septra) for 3 days. TMP/SMX is excreted in urine, and is therefore especially good for UTIs caused by

E. coli. Another first-line agent is Nitrofurantoin for 5 days.

UTIs caused by foley catheter infection should be treated with a third generation cephalosporin, or a quinolone.

Neonatal Meningitis:

Neonatal Meningitis is empirically treated with ampicillin PLUS an aminoglycoside (often gentamycin) or third generation cephalosporin, until culture confirms the pathogen.

Gram Negative Sepsis/Hospital-acquired Pneumonia:

Often treatment with a third (or fourth) generation cephalosporin is included, however the combination of antibiotics depends on the suspected organisms and the local resistance trends.

Resources and References

Gladwin, M., & Trattler, B. (2010). Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple. (4th ed.). Miami (FL): Medmaster Inc.

Anti-infective Review Panel. (2010). Anti-infective guidelines for community-acquired infections. (2010 ed.) Toronto: MUMS Guidline Clearinghouse.

Wanke, C.A. (2011). Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Retrieved June 16, 2011, from UpToDate

Topic Development

authors: Erica Rubin

reviewers: Dr. Eugenie Waters