Schistosoma

last authored: March 2010, David LaPierre

last reviewed: May 2010, Rosemary Drisdelle

Introduction

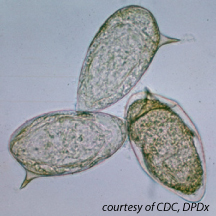

S. mansoni eggs, courtesy of CDC

Schistosomiasis is a serious, common disease, affecting 200-300 million people worldwide. However, it is considered a neglected disease due to the limited investment in research of its treatment.

Schistosomiasis is caused by blood trematodes (flukes). The three main species infecting humans are Schistosoma haematobium, S. japonicum, and S. mansoni. Two other species, more localized geographically, are S. mekongi and S. intercalatum.

Other species of schistosomes which parasitize birds and mammals, can cause cercarial dermatitis, or swimmer's itch in humans.

The Case of...

Epidemiology

Schistosoma mansoni is found in parts of South America and the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East; S. haematobium in Africa and the Middle East; and S. japonicum in the Far East. Schistosoma mekongi and S. intercalatum are found focally in Southeast Asia and central West Africa, respectively.

Lifecycle

Schistosoma adults are leafshaped, with a primitive, blind gut and suckers for attachment.

They are hermaphrodites. The females (size 7 to 20 mm; males slightly smaller)

The schistosomulae migrate through several tissues and stages to their residence in the veins. Oral tolerance reduces immune response.

Adult worms in humans reside in the mesenteric venules in various locations. S. japonicum and S. mansoni are found in the superior mesenteric veins draining the large and small intestine. S. haematobium most often occurs in the venous plexus of bladder, but it can also be found in the rectal venules.

Females deposit eggs in the small venules of the portal and perivesical systems. The eggs are moved progressively toward the lumen of the intestine (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) and of the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium), and are eliminated with feces or urine, respectively.

Under optimal conditions the eggs hatch and release miracidia, which swim and penetrate specific snail intermediate hosts.

Asexual multiplication in the snail produces two generations of sporocysts and culminates with the production of cercariae.

Upon release from the snail, the infective cercariae swim, penetrate the skin of the human host, and shed their forked tail, becoming schistosomulae.

Transmission and Infection

Human contact with contaminated water is necessary for infection by schistosomes. Cercariae are attracted to exposed skin. Attaching to the surface, they secrete arginine, which attracts more cercariae; and enzymes, which allow them to penetrate the skin of the human host. Within a couple of days they enter the blood, eventually arriving in the liver.

After maturing in the liver, the worms migrate to the intestine or bladder.

Animals such as dogs, cats, rodents, pigs, horses and goats, serve as reservoirs for S. japonicum, and dogs for S. mekongi.

Schistosomes live in the portal system, inducing eosinophil granulomas and IgE production caused by its eggs. It appears that a Th2 response instead of a Th1 response is a plan by the worm to survive. Upregulation of regulatory T cells reduces allergic response.

Schistosomes reduce immune attack by coating themselves in host proteins, and by regularly replacing their protective coat.

Clinical Manifestations

Many infections are asymptomatic. Acute schistosomiasis, or Katayama's fever, can occur weeks after the initial infection, especially with S. mansoni and S. japonicum. Manifestations include fever, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly, and eosinophilia.

The immune response to schistosoma involves a robust IgE response and eosinophil activation. Continuing infection may cause granulomatous reactions and fibrosis in the affected organs, which may result in manifestations that include:

- cystitis and ureteritis with hematuria, scarring, calcification, squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder (S. haematobium)

- colonic polyposis with bloody diarrhea (S. mansoni)

- portal hypertension with hematemesis and splenomegaly (S. mansoni, S. japonicum)

- pulmonary hypertension (S. mansoni, S. japonicum, more rarely S. haematobium)

- glomerulonephritis

- central nervous system lesions due to embolic egg granulomas

- hepatic perisinusoidal egg granulomas

- Symmers’ pipe stem periportal fibrosis

Diagnosis

Microscopic identification of eggs in stool or urine is the most practical method for diagnosis. Rectal and bladder biopsy may demonstrate eggs when stool or urine examinations are negative.

Stool

Eggs can be present in the stool in infections with all Schistosoma species. The examination can be performed on a simple smear (1 to 2 mg of fecal material).

Since eggs may be passed only occasionally or in small numbers, repeated testing or concentration (e.g., formalin-ethyl acetate) may be necessary.

Urine

Eggs can be found in the urine in infections with S. haematobium (recommended time for collection: between noon and 3 PM) and with S. japonicum. Detection is enhanced by centrifugation and examination of the sediment; quantification is also possible.

Treatment

Safe and effective drugs are available for the treatment of schistosomiasis.

The drug of choice is praziquantel for infections caused by all Schistosoma species. Oxamniquine may also be used for infections of S. mansoni if praziquantel is less effective.

Resources and References

CDC Medical Letter - treatments

University of Cambridge Schistosoma Research Group