Patient-Centred Clinical Method

last authored: Sept 2013, David LaPierre

last reviewed:

Introduction

The patient-centred clinical method (PCCM) is a conceptual approach to providing health care, is characterized by a full exploration of the patient's concerns within the context of their lives and mutually agreeing on the path forward, all within strong relationships with the health care team. It uses specific techniques to guide, with both philosophical and concrete means, the implementation of this approach.

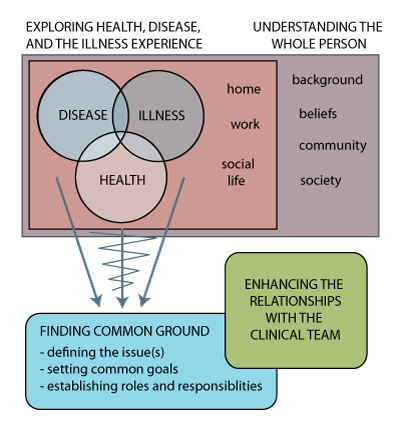

There are four major components of the PCCM, as follows:

- Exploring health, the disease, and the illness experience

- Understand the whole person

- Find common ground

- Enhance the relationships with the clinical team

Elements of the patient-centred clinical method

adapted from Stewart et al, 2013

The PCCM has strong value within the realm of clinical care, and therefore should also be included in undergraduate, postgraduate, and continuing professional developement. Accordingly, it is a helpful framework for assessing learner performance, and has been a rich source of research data, related to a variety of perspectives and outcomes.

The PCCM should be viewed within the context of the health care system and the members of the health care team that interact with the patient. Some members, such as a family doctor or primary nurse practitioner, will have oportunity for deep, ongoing relationships. Other team members may have infrequent, focused interactions with the patient. It is therefore helpful for the team to communicate and collaborate together, to deepen a collective understanding of the patient's background, their needs, and their desires.

This page describes an overview of each compoment, while providing links to further information, in greater detail.

Patient-centredness varies among patient encounters, though ideally increases over time and the clinician's career.

Exploring Health, Disease, and the Illness Experience

main articles: clincial assessment clinical reasoning illness

Students are well-trained in discovering and characterizing diseases that patients bring. This principally includes symptoms, signs, lab tests, and imaging.

Illness and disease are not synonyms. Clinicians can approach states of physiological disorder from an 'ontological' perspective, in which disease is an entity within, but also beyond, the person. Conversely, disorder can be viewed moreso as an inbalance between the person and the environment, with disease representing a collection of observations. Accordingly, in this view, it is difficult to discriminate among disease, person, and environment.

There is no question that patterns of cellular and tissue disorder exist, and that it can be helpful to characterize these according to a disease taxonomy. This helps in understanding treatments pathways, prognosis, and in sharing care. However, each patient will experience disease in a slightly different way - the illness experience. "If we are to be healers, we need to know our patients as individuals: they may have their diseases in common, but in their responses to disease, they are unique" (McWhinney, p 22, in Stewart et al, 2003).

There is error in focusing all clinical attention on the disease, which can leave the patient feeling like a "malfunctioning biological organism" (Toombs, 1992:106). This threatens not only the path to diagnosis, but also to therapy. Many conditions, such as chronic pain, fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, depression, anxiety, and addictions are profoundly affected by the internal experience, and can set up feedback cycles between thoughts, feelings, choices, and symptoms. "If [this pattern] is long term, destabilizing, and self-perpetuating, then the question of cause becomes much more complex than that of identifying a trigger. The trigger which initiated the process may be quite different from the processes perpetuating it. We have to consider the process in the organism that are perpetuating the disturbance. The key to enhancing healing may be in strengthening the organism's defences, changing the information flow or encouraging self-transcendence, rather than neutralizing the agent" (McWhinney, p 27, in Stewart et al, 2003).

A thorough exploration of the illness experience requires insight, tools, and practice. One helpful acronym is FIFE: Feelings, Ideas, Function, and Expectations.

- Feelings: what emotions have your experiences given rise to?

- Ideas: what do you think is causing this?

- Function: how has this affected your work? relationships? hobbies? self-care?

- Expectations: what are you hoping to leave here with?

It can also be very helpful to enter into the experience of illness through the arts, through means such as narratives of those who have suffered, poetry, films, or paintings. Also, the more stories a clinician hears, the greater their capacity to grow in awareness of what other stories could also hold. It is through this deepening of the imagination that our interview skills related to illness will grow.

Thoughts and feelings can both determine illness and be agents for therapeutic change.

As this occurs, it is critical to understand the experience of the patients.

Lastly, a clinician should understand the nature and concepts of health that patients bring, especially in regards to health promotion and disease prevention. For example, how do patients view the relative importance of quitting smoking, of doing screening, or taking steps to reduce the effects of disease?

A clinician should weave back and forth among these three components.

Exploration of illness and disease is the bedrock of a well-delivered interview

Understanding the Whole Person

main articles: personality family social determinants of health

A person does not exist in isolation; their experience of health, illness, and disease are profoundly impact by their personal development, their proximal context, and their distal context.

Personal development includes their childhood upbringing, the relationships they have and have had, their successes and failures, their beliefs.

The proximal context includes family, finances, education, leisure, employment, religion, and social supports. There is no roadmap for cultural understanding.

Immigration is increasing; there are over one billion migrants worldwide.

Distal context includes their community, culture, the state of the economy, their local health care system, the media they are exposed to, and the ecosystem.

Finding Common Ground

main article: clinical decision-making patient education

It is important to ensure the plan relates to your patient, at a specific point in time.

Finding common ground is of fundamental importance in the interview. Mutual decisions need to be made in regards to understanding the problems, the goals, and the roles that each will play.

In order to find common ground, health, disease, and illness must be comprehended, and a plan needs to be negotiated. This can take a significant amount of time, and may not be possible within one visit.

Each visit provides opportunity for brief messaging regarding health.

Good outcomes, from the patient and the clinician perspectives, appears to be most associated with finding common ground (Stewart et al, 2000).

Information-sharing should be open and two-way.

Common ground is crucial to therapy, though it can be a signficiant challenge to reach. The clinician must be versed in clarifying understanding, particularly around misconceptions, in quieting fears, in building hope, and by resolving obstacles within the patient. This represents the realm of motivational interviewing.

There needs to be a joining of the perspectives of the clinician - usually focused on disease - and the patient - usually focused on illness.

Enhancing the Relationships with the Clinical Team

main article: the patient-clinician relationship the health care team

Relationships can be healing, or harmful.

There is signficiant risk if a clinician does not enter into the emotional experience of suffering alongside the patient. Firstly, a cool, detached stance can hinder formation of a therapeutic relationship, compromising trust and honesty from the patient. Next, as humans, we normally have no choice but to be affected by suffering. To pretend otherwise can lead to unhealthy patterns in the clinician-patient relationship, such as avoidance or anger. Equally damaging, it can result in desructive patterns within the clinician, such as guilt or helplessness.

There is certainly need for appropriate sharing of the experience of suffering; being too close can be dangerous in a variety of ways. This takes courage, therefore, but also self-awareness, reflection, and the sharing of the clinician's journey with peers or mentors to ensure it is unfolding well.

Important aspects include:

- compassion, caring, and empathy

- trust

- sharing of power, where there is a levelled playing field in determining the path forward

- healing

- self-awareness

- transference and counter-transference

Relationships require time, and contuinity certainly helps strengthen the patient-clinician relationship.

Potential Misconceptions

The PCCM, when used well, should not be focused predominantly on the illness experience, or the patient's agenda.

It need not take an overwhelming amount of time; research has shown an effective patient-centred encounter is

The increasing role of evidence-based medicine in clinical care can threaten the therapeutic relationship, if the focus strays too heavily towards facts and data. However, this is not necessarily the case. Good clinical care depends on relevant evidence, often informed by quality clinical guidelines, and both clinician and patient require sufficient knowledge to make informed decisions. How this knowledge is researched, shared, and utilized matters, though there is no reason that this cannot be fully embedded within the PCCM.

Support for the PCCM

The PCCM is associated with improvements in patient satisfaction, adherence, symptoms, and even physiologic status, such as blood pressure and diabetic control (Greenfield et al, 1988). It is also associated with greater physician satisfaction and fewer complaints (ref). Lastly, there may be dcreased diagnostic testing and referrals (Stewart et al, 2000).

Assessing Use of the PCCM

Learners require information, opportunity for structured practice, and feedback as they learn to apply and hone the PCCM. This growth requires self-awareness in regards to understanding the impact of the internal, subjective world, and the contexts in which the learner exists (ie experiences, values, beliefs).

"tell me one thing about this patient that I didn't know" - a good line to use with residents.

Resources and References

Stewart et al. Patient-Centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method. 2003.

Greenfield S et al. 1988. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 3(5):448-57.