HIV and AIDS

last authored: April 2012, David LaPierre

last reviewed:

Introduction

Since being recognized in 1981, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and the resulting disease AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) have become one of the biggest global infectious disease threats we face, with over 75 million infections. While prevention of transmission, which is most frequently spread via sexual intercourse, from mother-to-child, and by sharing needles, is one of the greatest goals of HIV care. Another goal is to tackle the stigma of this disease, to encourage testing and dialogue, among partners and with health care providers.

Shame, by Brett Vair

HIV infections often cause acute symptoms, lasting for a few weeks after infection. These resolve and usually lead to an asymptomatic phase, lasting 2-7 years. HIV infects specific cells of the immune system, and as disease progresses the symptoms of AIDS appear through different types of local and systemic infections.

HIV is alomst universally fatal without treatment. However, various types of medications have reduced HIV to a chronic disease in many circumstances. The world continues to improve access to HIV medications, particularly for those in resource-poor areas who need them most.

Epidemiology

According to the UNAIDS 2008 report, there are:

- 33 million people living with HIV in the world, 2 million of these children

- 2.7 million new infections, 370 000 of these children

- 2 million AIDS deaths in the world, 270 000 of these children

UNAIDS maps detail the global distribution of HIV infections and deaths. Almost two thirds of people with HIV live in sub-saharan Africa, where almost three quarters of deaths due to AIDS occur. The prevalence rates in sub-Saharan Africa in 2005 approached 6%, while in North America rates were 0.7%. Global prevalence was 1.0%. Prevalence has begun to decline since 2000, following the massive outpouring of aid. From 2000-2007 there was an almost 10x increase of money for AIDS.

Canadian Rates

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, a total of 61,423 cases of HIV and 20,493 cases of AIDS had been reported in Canada from 1985 to June 2006.

Transmission and Infection

HIV may be transmitted in various ways but is mainly spread through sexual activity or intravenous drug use.

Sexual transmission rates are low - approximately 0.3% per contact, but this can be increased by:

- increased viral load

- cervical ectopia

- oral contraceptive use

- pregnancy

- intact foreskin in men

- genital ulcers

Parenteral transmission is the most effective, with rates approaching 90%. Congenital infection, either before, during or after birth, occurs on average in 20- 30% of babies born to HIV +ve mothers. Transplacental transmission is the most common mode of infection.

HIV can also be an occupational hazard - needle-stick incidents carry with them a risk of 0.2%.

Predominant modes of infection vary across region. Various high-risk behaviours are more common in various parts of the world. Although epidemics do extend into the general population, they remain highly concentrated around certain groups.

In Canada, people who had contracted AIDS

|

for women who had contracted AIDS

for children who had contracted AIDS

|

source: Public Health Agency of Canada HIV and AIDS surveillance report, 2006

The HIV Virus

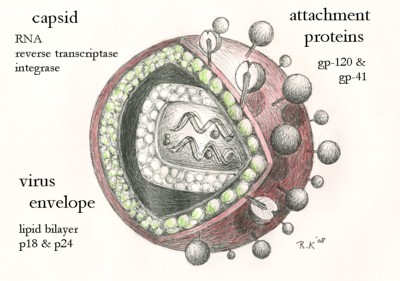

HIV is an enveloped RNA retrovirus roughly 120 nm in diameter - 60 x times smaller than RBCs.

It contains two copies of single-stranded RNA, with 12 genes (I think) coded in about 9,500 base pairs within a virus capsid. The capsid also contains virus proteins including reverse transcriptase and integrase. These are surrounded by the nucleocapsid, formed by proteins p24 and p17.

Cell surface glycoproteins GP-120 and GP-41 facilitate binding and fusion with CD4+ cells. The envelope is host-derived.

Vif, Vpr, Nef, and viral protease are also included within the virus.

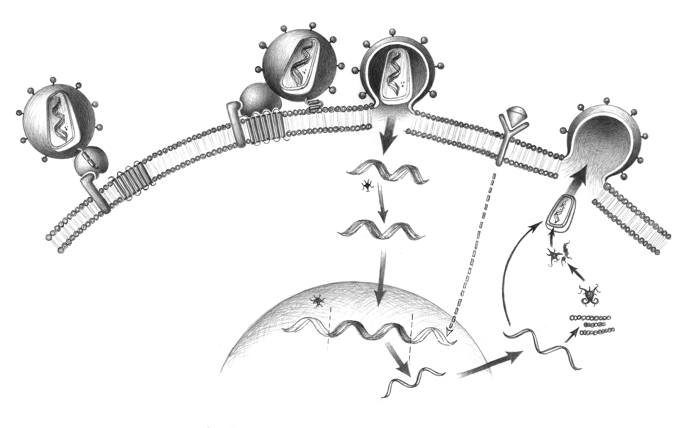

HIV infects CD4+ cells (helper T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages) via binding of surface protein gp-120 to CD4 and chemokine receptors CXCR4 or CCR5. This induces a conformational change in gp-41, which leads to membrane fusion andinjection of the capsid.

Once inside, viral RNA is converted into DNA by reverse transcriptase. The DNA then enters the nucelus and becomes integrated within the chromosome through action of viral integrase. RT is error prone and enhances virus genetic diversity.

Viral reproduction can begin at once, or it may remain latent for years until activation of the cell by cytokine activity (ie TNF). Following viral transcription, mRNA is transcribed into viral proteins, involving protease. Other copies are assembled into newly developing viral particles. Mature virions are released by budding. If the viral load is high enough, cell lysis can occur.

Prevention

Vertical transmission is reduced to <1% if antiretroviral therapy is given during pregnancy.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) can be extremely effective for people exposed to blood or body fluids. It should be provided as soon as possible; effectiveness is much lower if started 36-72 hours post-exposure. The HIV status of the source is very helpful, and should be determined before beginning PEP. Treatment should be started especially if the clinician believes the source may in the window period of acute infection, or is experiencing terminal AIDS, as these are times of high viral load.

The preferred regimen is zidovudine + lamivudine (combivir); tenofivir + lamivudine, or stavudine + lamivudine are alternatives. A protease inhibitor may be added if the source is on ART and resistance is evident.

Treatment should be given for four weeks. The commonest side effects are nausea and fatigue.

Baseline and 3 month testing should be carried out.

Diagnosis

- diagnostic testing

- history

- physical exam

- lab investigations

Diagnostic Testing

Early identification of disease is critical to protecting sexual partners in sero-discordant relationships, preventing vertical transmission, reducing rates of opportunistic infections, and equipping people to live aware of their status.

All women should be tested during pregnancy, as often as possible.

|

Point-of-Care TestingHIV testing is increasingly offered as a part of primary care using rapid, point-of-care testing.

These tests are quite sensitive, meaning a negative result strongly suggests lack of HIV antibodies in the blood.

However, a low specificity requires that positive tests be followed up with more sophisticated laboratory testing to confirm results. Patients should be informed of the risk of false positives during informed consent.

The tests shown on left are two different tests used in sub-Saharan Africa. |

Laboratory Testing

Diagnosis is primarily established by detection of serum or salivary antibody to HIV using enzyme-immunosorbent assay (EIA).

Confirmation is done using Western blotting, with different bands representing different strains. PCR is done to assess viral load.

Most tests are very sensitive, although Recent infection can lead to negative serology. During the window period of 1-3 weeks before antibody development, testing can be done on HIV RNA or p42 core antigen.

History

HIV will often be diagnosed by screening. Asking about potential modes of transmission (sexual history, IV drug use, transfusions) can provide indication for screening.

HIV/AIDS can manifest in various ways, as described below (clinical manifestations). Inquire into acute infections, as well as type B symptoms: fever, chills, night sweats, appetite and weight.

Physical Exam

Head and Neck

thrush, gingivitis, leukoplakia (due to EBV)

dermatology

rashes, Kaposi's sarcoma

Lab Investigations

Routine Tests

PAP smear |

HIV investigations

Other Pathogens

|

Clinical Manifesations

Untreated HIV infection usually results in a slow but variable progression. About 50% of adults will develop AIDS within 10 years, 30% will have milder symptoms, while 20% will be entirely asymptomatic. (outside site: Toronto General overview of AIDS progression).

- acute retroviral

syndrome - asymptomatic

phase - early sympt.

phase - advanced sympt.

phase - other chronic

diseases - pediatric

disease - stigmas

Acute retroviral syndrome

Acute seroconversion illness can result from high level virus reproduction and viremia, with widespread infection of lymphoid tissue. It affects over half of infected people, with a mono-like illness occurs 3-6 weeks after infection, lasting a few weeks.

Signs and symptoms include:

- acute fever

- rash

- lymphadenopathy

The intact immune system can readily deal with this, and symptoms soon subside.

Asymptomatic phase

Following containment of virus, clinical latency with no overt symptoms usually lasts 2-7 years. Rates of progression vary greatly, and adolescents progress more slowly than older adults.

Persistent lymph node enlargement is common though not associated with progression or development of lymphoma.

Thrombocytopenia can result, including as ITP. Pancytopenias of any type are possible.

People tend to lose approximately 100 cells/mm3 cells per year.

People usually are unaware of their infection until counts fall below 200 cells/mm3.

Early Symptomatic Phase

People with moderate immunodeficiency (CD4 200-500 cells/mm3) may show decreased cellular and humoral activity.

Opportunistic infections (OIs) vary considerably in time of onset and CD4 count. Initial infections tend to respond well to therapy.

Infections of the skin or oral/genital mucosa may be the first signs of infection. These include:

- pulmonary tuberculosis

- polydermatomal shingles

- recurrent herpes simplex

- oral or vaginal candidiasis

- oral hairy leukoplakia

Bacterial pneumonias (especially Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae) are 3-4x more common.

Advanced Symptomatic Phase

As CD4 count drops, high viremia is followed by lymphoid destruction and diminished immune response.

Without treatment, full blown AIDS occurs on average in 7-10 years. However, in people with decreased immune function to begin, it can occur in as little as 2 years.

Nonspecific symptoms herald the beginning of full-blown AIDS. These include fever, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, or diarrhea. These can persist for months without any identifiable agents.

Kaposi's sarcoma, non-hodgkins, brain lymphomas are seen, as is AIDS dementia complex (resembles Alzheimer's) mood disturbances, movement disorders, others.

Infections of the skin, oral mucosa, esophagus, genitals, nervous system, lungs, and GI tract become more common. Life threatening OIs tend not to occur at CD4 counts above 200 cells/mm3.

Later, more serious opportunistic infections include:

Bacteria

Viruses |

Fungi

protozoa and helminths

|

A Clinical Guide to Supportive and Palliative Care for HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa

Other Chronic Diseases

Pediatric Manifestations

Signs and symptoms in infants and children often occur within the first year and usually within the first two years. They include:

- failure to thrive

- lymphadenopathy

- hepatomegaly

- opportunistic infections

- chronic interstitial pneumonitis

- Pneumocystis jirovecii

- recurrent or persistent thrush

- encephalopathy

Stigmas

there is much discrimination attached to HIV diagnosis, affecting patients and their families.

Treatment

Treatment in HIV/AIDS depends on healthy living, reducing the risk of acquiring further infections, prophylaxis of opportunistic infections, and anti-retroviral therapy (ART). There are important, and difficult questions on when to start ART, as discussed below.

- anti-retroviral therapy

- starting ART

- prophylaxis of opportunistic infections

The goals of anti-retroviral therapy are to reduce viral load to undetectable levels, restoring immune function, improving quality of life, and reduce HIV morbidity and mortality.

As long-term impact depends on adherence, decisions on when and what drugs are used should be made with the patient's full participation.

Combination drug treatments are called highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) include at least three drugs. While guidelines vary considerably, across geography and time, in general, a 2 NRTIs + NNRTI or PI are used in HAART. Drug classes are ideally spared for times where mutation occurs.

Early treatment appears to offer morbidity benefit (Kitahata et al, 2009).

Nucleoside analogue RT inhibitors (NRTIs)

|

Non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs)

Fusion inhibitor

Integrase inhibitors

|

Protease inhibitor (PIs)

CCR5 inhibitors

Maturation inhibitors |

Side effects

Common, and serious, side effects of ART include:

- hepatotoxicity

- hyperglycemia

- lipodystrophy/fat maldistribution: loss from face and limbs

- hyperlipidemia

- increased bleeding in people with clotting disorders

- osteonecrosis, osteopenia, osteoporosis

NRTIs: lactic acidosis/hepatic steatosis, lipodystrophy

- abacavir: hypersensitivity reaction (specific HLA B 57-1)

- didanosine: GI intolerance, pancreatitis, peripheral neuropathy

- stavudine: PN, pancreatitis

- tenofovir: headache, GI intolerance, renal impairment

- zidovudine: headache, GI intolerance, bone marrow suppression

NNRTIs: rash, drug-drug interactions

- nevirapine: hepatotoxicity, Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- efavirenz: neuropsychiatric, likely teratogenic

Protease Inhibitors: hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance and diabetes, lipodystrophy, elevated liver enzymes, possible increased bleeding risk in hemophiliacs, drug-drug interactions

- amprenavir and fosamprenavir: GI intolerance, rash

- atazanavir - hyperbilirubinemia, PR interval prolongation

- indinavir: nephrolithiasis, GI intolerance

- lopinavir/ritonavir: GI intolerance

- nelfinavir: diarrhea

- tipranavir: GI intolerance, rash, hyperlipidemia, hepatotoxicity

Fusion Inhibitors

- enfuvirtide: hypersensitivty reactions, increased risk of bacterial pneumonia

Starting ART

There is ongoing debate regarding whether to treat cell count or viral load.

Antiretroviral treatment can begin immediately after diagnosis, and is recommended by many to prevent transmission and reduce infection rates. However, there are also drawbacks to this approach, including drug resistance and significant side effects, as described, which often lead to decreased adherence.

Genotyping should be done, if possible, to determine the potential for resistance prior to starting antiretrovirals.

Treat all patients with AIDS-defining opertunistic infections, or severe symptoms. Other suggestions regarding treatment include:

- absolutely everyone with CD4 <200 cells/mm3

- strongly offer to those with CD4 201-350 cells/mm3

- consider in those with CD4 350-500 cells/mm3 and viral load (VL) >100,000 copies/ml

- defer in those with CD4 >500 cells/mm3 and VL <100,000 copies/ml

Drug resistance can limit future treatment options, and it can be important to wisely sequence drugs, saving some for future use if/when resistance becomes a problem.

Prophylaxis

Prophylaxis of opportunistic infections depends on local prevalence of pathogens, success in their eradication in patients, and the potential consequences of their proliferation, as well as adverse effects and costs of the medications.

Primary prophylaxis is used to prevent initial infections, while previous infections are followed by ongoing treatment to prevent relapse or recurrence (maintenance therapy/seconary prophylaxis, respectively).

Immunizations include:

- IPV and Td: every 10 years

- influenza: yearly

- pneumococcus: every 5 years

- hepatitis A and B

- MMR (if titres are low)

- avoid OPV, BCG, and yellow fever vaccines, as they are live

Commonly used medications, and their targets, include:

- bacteria/PCP <200 : TMP/SMX (dapsone if allergy)

- cryptococcus <50

- histoplasma

- coccoides - fluconazole

- candida

- toxoplasma: TMP/SMX and avoid sources of contamination (soil, kitty litter, raw meat)

- MAC - azythromycin, clarithromycin

- pneumococcus: pneumovax vaccine

- mycobacteria - isoniazid

- hepatitis A/B vaccines

- HSV - acyclovir

- CMV - cyclovir

Impact of HIV on Patients, Families, and Communities

Need emotional, nutritional, social, and spiritual health efforts.

Partnerships with Patients and Caregivers

Loss to follow-up is a huge problem: stigma, poor resources, others.

Agreement on care plan is essential to strengthen adherence, improving outcomes

HIV/AIDS has brought critical problems for societies to address:

- chronic/palliative care capacity

- availablity/legality of medication for pain

- impact of extended illness and death on family and community

Basic care package for people in Africa

- cotrimoxizole

- malaria bed net

- clean water and water vessels

- micronutrients

- TB testing

Team Approach

clinicians, community, family members, 'expert patients'

Self-Management

need to set good goals for patients and caregivers.

- adherence, clinic visits, nutrition, etc

Resources and References

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

Hammer S et al. JAMA 2006: 296:827-843.

Kitahaya et al. 2009. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. NEJM. 360(18):1815-26.

University of Utah's WebPath AIDS pathology images

WHO Post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection