Acute Abdominal Pain

last authored: April 2012, David LaPierre

last reviewed:

Introduction

Acute abdominal pain refers to pain with sudden onset and duration of less than 48 hours, while chronic abdominal pain lasts longer than two weeks.

Acute abdominal pain is very common, with up to 20% of people experiencing abdominal pain in the past year. Up to 90% of cases are of minor significance and resolve in 2-3 weeks on their own. However, there are many life-threatening causes of abdominal pain, leading to potential consequences such as bowel performation, ischemia, or sepsis. As such, clinicians need to have a high index of suspicion for concern when evaluating abdominal pain.

The Case of Mr. Reclu

Mr Reclu is a 54 year-old man presenting to the emergency department with a 2 hour history of intense, constant epigastric pain which began suddenly an hour after lunch. It does not radiate anywhere. He is otherwise healthy, other than intermittent indigestion. He does not take any medications.

- what could be causing his pain?

- what further questions do you ask? what physical exam do you perform?

- what tests do you order?

Differential Diagnosis

The most common diagnosis is "nonspecific abdominal pain", usually a self-limited condition with no identifiable cause. However, as many of the potential conditions require urgent surgical involvement, a high index of suspicion is required.

A variety of body systems should be considered, including gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, genito-urinary, obstetric/gynecologic, and musculoskeletal.

***Life-threatening conditions are marked with an asterisk; ensure you consider and rule these out, either clinically or through testing.

epigastric

right upper quadrant

right lower quadrant

|

left upper quadrant

left lower quadrant

periumbilical or diffuse

|

History and Physical Exam

Begin with a rapid assessment of whether the patient is stable or unstable.

- history

- physical exam

History

ChloridePP

Character: colicky pain builds and subsides, suggesting hollow organ pain. Sharp, stabbing pain suggests peritoneal involvement.

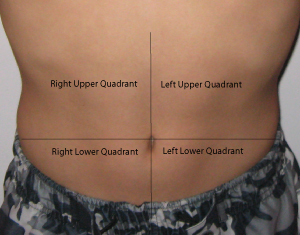

Location

epigastric pain can come from the stomach, duodenum, or pancreas.

right upper quadrant pain can come from the biliary tree or liver (cholecystitis)

periumbilical pain can come from the small intestine, appendix, or colon.

sacral pain can come from the rectum.

hypogastric pain can come from the colon, bladder, or uterus.

Onset: Sudden, severe pain suggests perforation (duodenal ulcer) or ischemia, such as can occur with ovarian cyst (perforation or tortion).

Radiation: Pancreatic pain tends to radiate through to the middle of the back. Gallbladder pain tends to radiate around to the right side. Renal pain starts in the flank but can radiate to the groin.

Intensity: rate from 1-10, with 10 being the most severe pain the patient has experienced.

Duration: waves of pain suggest rhythmic muscle contractions, such as those of peristalsis, are involved.

Events Associated: A pertinent review of systems based on the differential.

Provoking and Palliating Factors: The impact of certain behaviours can point to system of origin. Changes with eating, bowel movements, or vomiting suggest pain is GI in origin. Increased pain with exertion suggests cardiac causes.

Associated Symptoms

- nausea/vomiting: pain reflex, gastroenteritis, bowel obstruction

- constipation

- obstipation

- diarrhea

- tenesmus

- fever and chills: inflammation or infection/sepsis

- distension or bloating: intermittent with IBS, progressive with mass or ascites

- weight loss: (?malignacy or IBD)

- change in bowel habits: malignancy

- rectal bleeding: bright red, melena

- jaundice: liver, biliary tree, gallbladder or hemolysis

- urinary symptoms: frequency, dysuria, hematuria

in women:

- vaginal discharge: PID

- last menstrual period

- pregnant?

past history

- previous episodes

- previous surgery

- sexually transmitted infections

- medications

- constipation (potentially leading to obstruction)

Family history

- inflammatory bowel disease

- cancer

Medications

Social History

- smoking, alcohol, drugs

Physical Exam

The abdominal exam can reveal important clues, and should be started with simple inspection of the state of the patient.

Weight loss, pignmentation, and signs of dehydration are all possible.

Auscultation can be used to assess bowel sounds and discover bruits.

Palpation should be done gently, starting away from area of pain. Percussion can be used to measure organ size and determine presence of ascites. A pulsatile mass suggests aneurysm, and peripheral pulses should be felt.

Peritonitis is an important finding. Signs include:

- involuntary guarding

- rigidity while taking a deep breath (the most sensitive test)

- percussion tenderness may be provocative.

- absent bowel sounds (over 2 min)

- rebound tenderness (though this is not sensitive and unnecessarily painful; avoid it).

Right upper quadrant pain can sometimes be associated with a palpable mass in Crohn's disease.

Rectal examination is important to rule out tumour, diverticulitis, and other conditions.

Pelvic examination should be done to rule out pelvic infammatory disease.

Investigations

- lab investigations

- diagnostic imaging

Lab Investigations

In an emergency setting, bloodwork may be sent off before clinical evaluation if the situation appears urgent. Tests include:

CBC: anemia, infection, high platelets in inflammatory disease.

electrolytes, glucose: ketoacidosis, hypercalcemia

liver labs: hepatic or biliary tract involvement

amylase and lipase: pancreatitis

coagulation profile: especially important for people on anticoagulants

b-HCG for pregnancy

X-match

tox screen

fecal occult blood test can be used to evaluate potential upper GI bleeds

Diagnostic Imaging

Ultrasound is a fast, safe, and accurate modality to evaluate acute abdomen (Lameris et al, 2009)

Abdominal plain films may detect:

- air under the diaphragm or retroperitoneally from perforation

- dilated bowel loops and/or air-fluid levels from obstruction

- fecal loading from constipation or obstruction

ECG should be done to exclude MI.

CT scans can be very revealing though do require specific protocols for

Endoscopy can be used to detect peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, or tumours, but is contraindicated if perforation is suspected.

barium enemas

HAIDA scans can be used to evaluate gallbladder conditions, but takes time

ultrasound

Management

If the patient is unstable, prompt attention to the ABC's is required. Provide IV fluids as necessary to control heart rate and blood pressure, as well as oxygen if needed. Electrolytes should be replaced.

Imaging should be postponed until the patient is stable.

The patient should be made NPO (should not eat or drink) until the situation is well-understood.

Pain medications should be provided after brief examination but before a detailed history and physical exam.

Further management will depend on the identified cause for the pain.

Pathophysiology

Abdominal pain results from thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimulation of specific sympathetic nervous system receptors. Visceral neurons are C type, resulting in variable sensation and localization. Peritoneal pain is carred by A and C types, resulting in sharp, localized pain.

Abdominal pain can step from structures in the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, peritoneal, musculoskeletal, and pelvic systems.

Parietal PainParietal pain originates in the parietal peritoneum and is caused by inflammation. Steady aching pain is more severe than that of visceral pain and can be more precisely localized, as it is carried by somatic nerves. It is typically made worse by movement or coughing, and people tend to want to lie still. Rebound tenderness is present. |

Visceral PainVisceral pain originating in internal organs and structures tends to activate vagus and splanchnic autonomic nerves, with diffuse difficult to localize, typically midline pain. If mucosal, pain tends to be steady - if crampy, visceral pain suggests intraluminal problems.

|

Referred PainReferred pain originates at one location but is felt in another site, superfically or deeply, within or near the same spinal level(s). Abdominal pain can be referred from the thorax, abdomen, pelvis, or spine.

|

Additional Resources

Topic Development

created: David LaPierre, 2008

authors: DLP, Aug 09

editors:

reviewers: